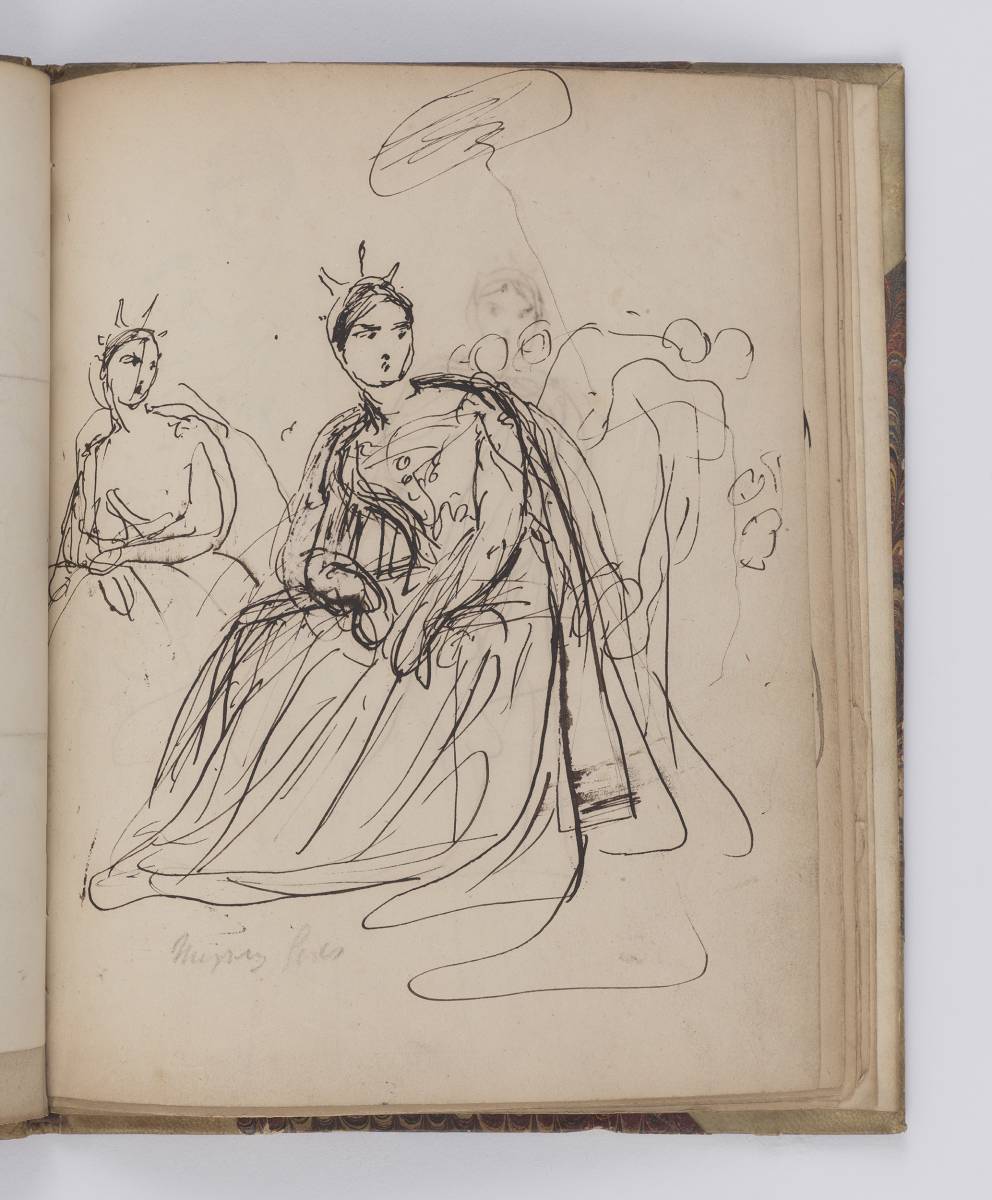

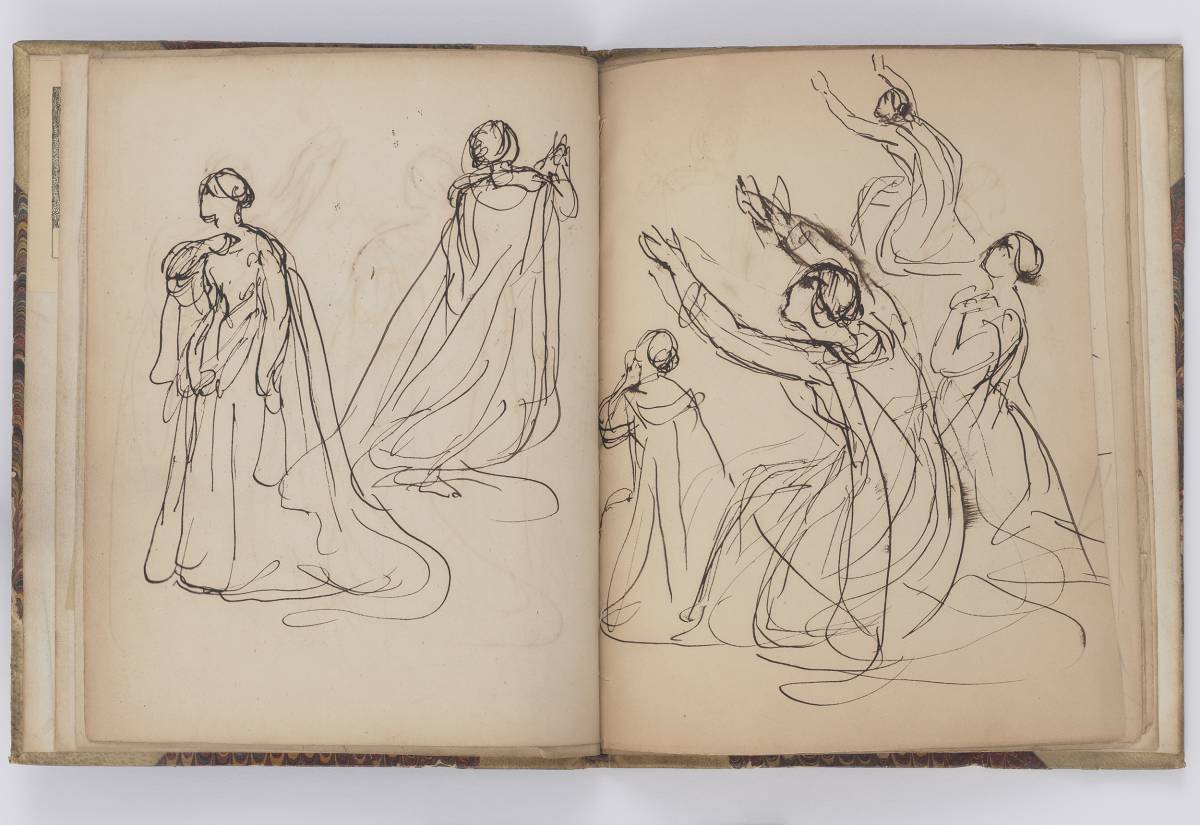

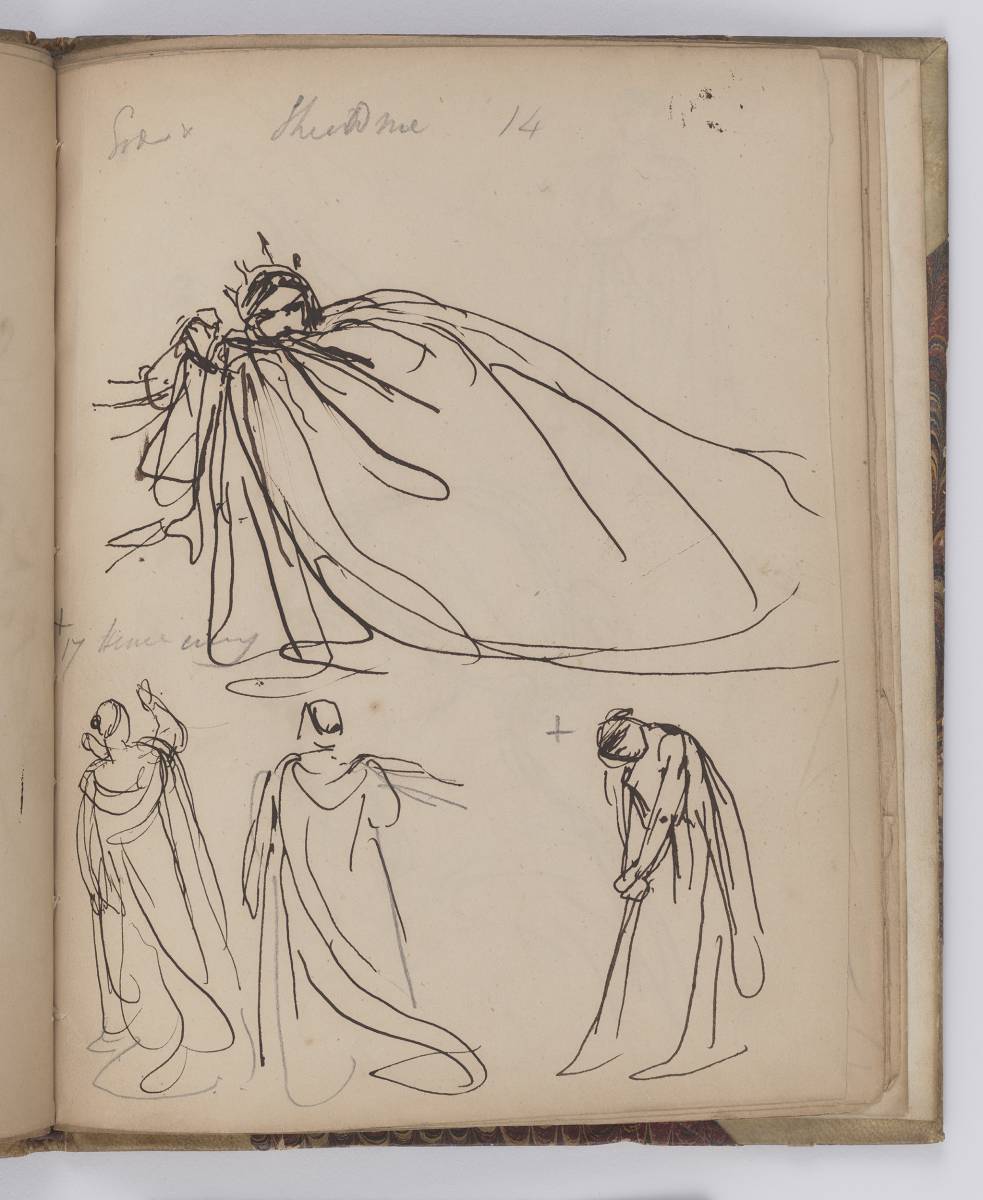

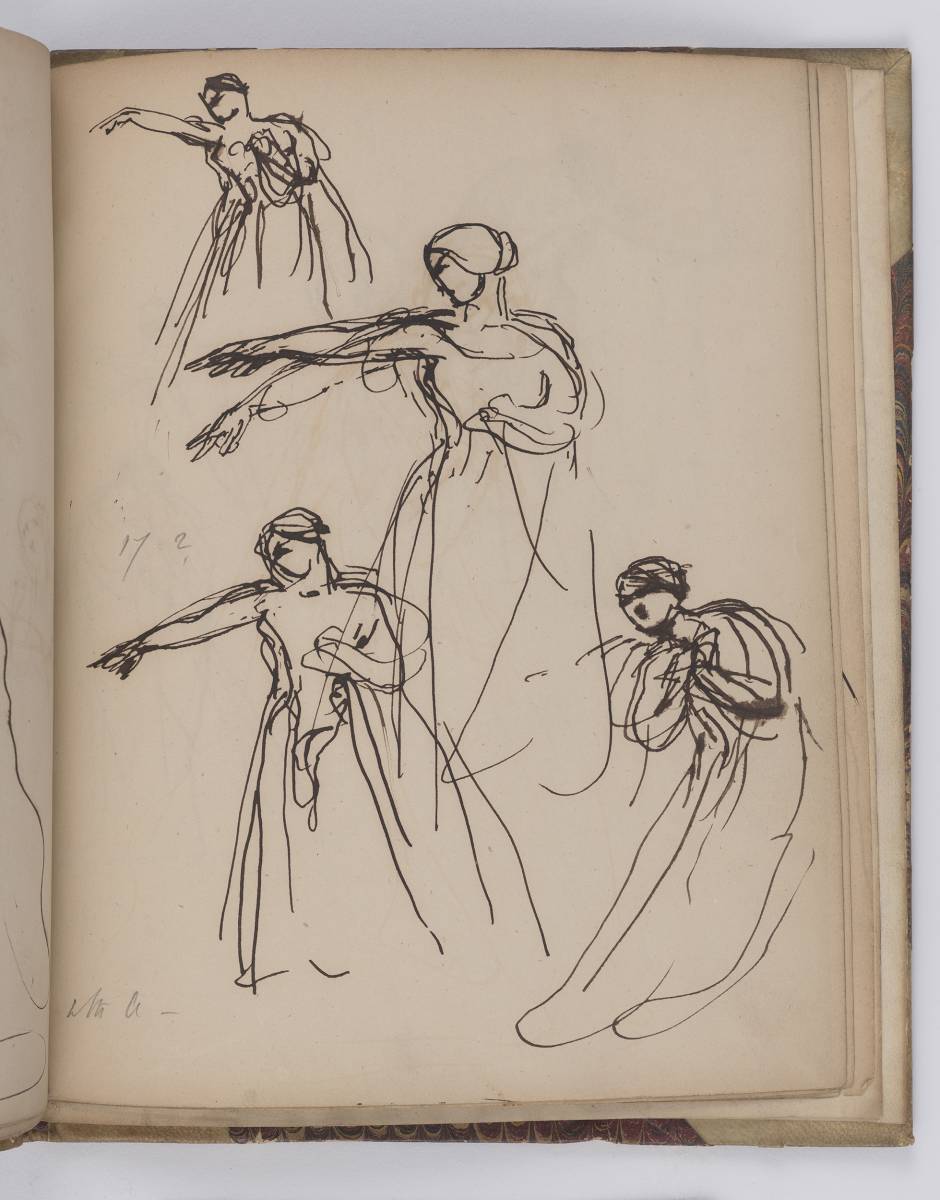

This sketchbook is filled with drawings showing the soprano Adelaide Kemble singing in her most celebrated roles, made by the successful portrait painter John Hayter, the studies relate to a commission by John Bentinck, 5th Duke of Portland for a series of portraits of Kemble still at Welbeck Abbey. Clearly made in the theatre during live performances, the rapid, kinetic studies capture Kemble as she essayed two of the great heroines of early nineteenth-century Italian opera: Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide and Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma. Made during the 1842 season Hayter captures Kemble’s remarkable stage presence and celebrated dramatic interpretation of the roles. The sketchbook belonged to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and contains a warm presentation inscription from his brother, William Michael Rossetti to the aesthete and lover of Walter Pater, William Money Hardinge.

Adelaide Kemble came from a distinguished theatrical dynasty, she was the daughter of the actor Charles Kemble, niece of the leading tragedians John Philip Kemble and Sarah Siddons, and sister of the notable abolitionist Fanny Kemble. Trained in London under the tenor John Braham and in Italy under the great soprano Giuditta Pasta, Kemble sang at La Scala, Milan, in 1838, and the same year made her operatic debut as Norma in a production at La Fenice in Venice. After successfully touring in Italy, Kemble returned to Britain in 1841, where she had a brief but spectacular career. Kemble sang at a charity concert at Stafford House, London, in June 1841, and appeared in an English version of Norma in November at Covent Garden. She sang Elena in Saverio Mercadante’s Elena da Feltre in January 1842, Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro and Caroline in Cimarosa’s Il matrimonio segreto, as well as appearing in Bellini’s La Sonnambula and Rossini’s Semiramide. In December 1842 Kemble gave her final performance as Norma at Covent Garden. Kemble had many admirers, including the fifth duke of Portland.

This volume contains pages from the pocket sketchbook used by Hayter towards the end of the 1842 season and captures Kemble in her roles as Semiramide and Norma. Kemble was celebrated for her stage presence and acting abilities and Hayter’s dynamic studies capture Kemble in a series of dramatic moments from the two operas. The kinetic pen and ink drawings fill each page, frequently producing a rapid sequence of closely related studies of Kemble, producing a remarkable record of her performances. Both the scheming Babylonian queen, Semiramide and the tragic Druid priestess, Norma offered plenty of scope for Kemble’s acting and Hayter delights in showing Kemble in moments of heightened drama. As Charles Pascoe, the nineteenth-century critic noted: ‘Adelaide Kemble was the first to accustom English playgoers, not merely to admit and enjoy the expression of passion in music, but to require of the artist impassioned acting as well as musical feeling. Judged even by the exceptional standard of Pasta, Malibran, Schroeder, and Grisi, Adelaide Kemble was able to maintain her own high place on the operatic stage, whether as a singer of an actress.’[1]