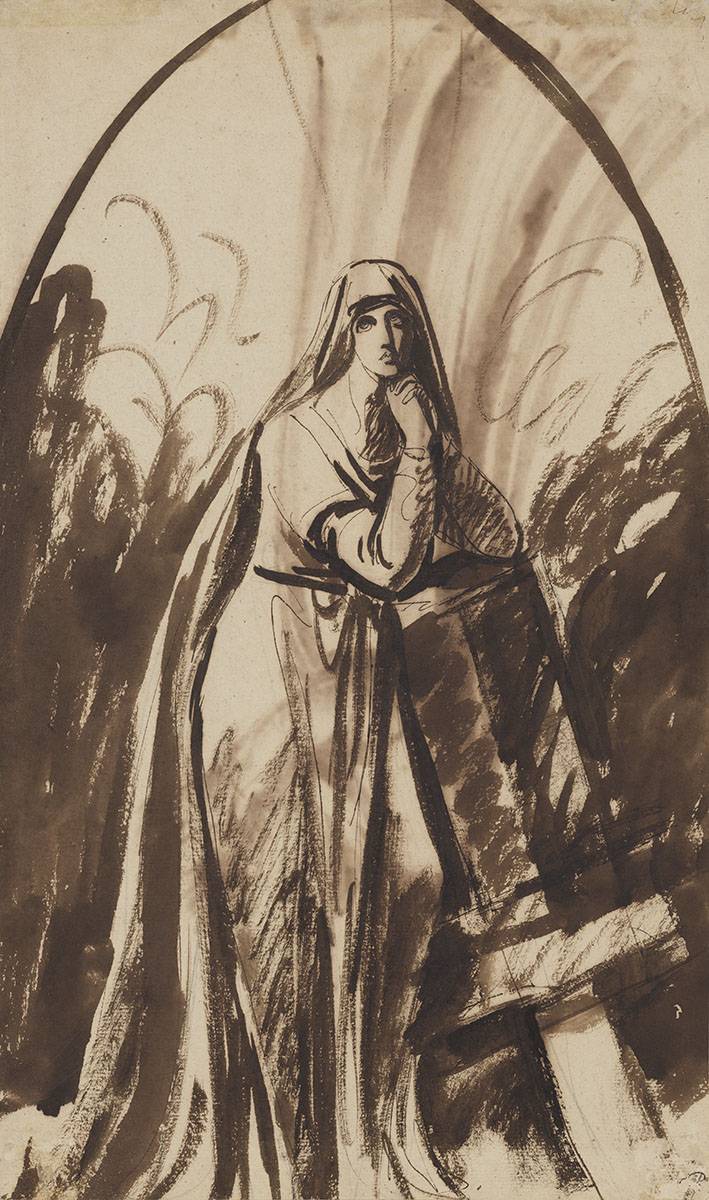

This grand, richly inked drawing was made by George Romney in preparation for one of the most ambitious commissions of his career, a proposed altarpiece of the Mater Dolorosa for the Chapel of King’s College, Cambridge. The project offered Romney the opportunity to experiment on paper, producing emotionally charged historic compositions in brown ink on a large scale.

In the winter of 1775, following his return from Rome, Romney took over the lease on Francis Cotes’s spacious studio, fashionably located at No. 24 Cavendish Square, London. The move was a bold one – Romney set himself up in direct competition with the leading portrait painters in the capital, Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Romney’s friends helped initiate the artist’s rapid ascent as one of the most notable portrait painters in the capital. In 1776, the dramatist Richard Cumberland, a prominent early patron, dedicated his Ode to the Sun to the artist, praising him as ‘among the first of his profession.’ Dr Johnson attributed Romney’s rise in popularity to Cumberland’s poem. The first commissions for portraits were made by significant figures in London society: Sir George Warren; Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond and George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick. Within a brief time, Romney’s rooms were crowded with wealthy patrons accompanied by family members and friends, which in turn generated further commissions.

Romney’s greatest ambition, however, was to be a history painter; in the words of his friend John Flaxman: ‘His heart and soul were engaged in the pursuit… of historical and ideal painting.’ Thomas Orde, later the 1st Lord Bolton, who had purchased a pair of allegorical paintings, Mirth and Melancholy, at the Society of Artists in 1770, attempted to secure a commission for a history subject for Romney in 1776. According to John Romney’s memoirs of his father, Orde expressed the desire to present an altarpiece for the chapel of his alma mater, King’s College, Cambridge. He desired a painting ‘of a solemn but splendid effect’ and suggested the theme of a Mater Dolorosa, the image of Mary mourning at the cross. The idea was that Romney would produce a grand, standing figure personifying grief, much in the manner of Orde’s Melancholy. As was his habit with his most stimulating commissions, Romney produced multiple drawn studies as he prepared to undertake the final painting. In the end Orde’s project was pre-empted by Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle, who donated a Deposition thought to be by Daniele da Volterra (now attributed to Girolamo Siciolante de Sermoneta). According to John Romney, his father’s altarpiece ‘was in a state of great forwardness’ when this happened. Romney lost the fee of 100 guineas and the prestige of having his work in such a prestigious location.

As Alex Kidson has noted, Romney’s surviving drawings for this project are surprisingly various. Romney’s method was to settle on a compositional motif and then repeat it continually, but in the case of this commission, the surviving drawings show a considerable degree of variation in the conceptualisation. It was possibly a combination of the high-profile location of the painting and the subject-matter which caused Romney to experiment more than normal. The present sheet is one of the grandest and most fully realised of the drawings made for this project and shows how Romney tried to adapt the language of patrician portraiture for historical work. Romney shows the Virgin full length, standing in a landscape, leaning on a plinth, which, on closer inspection is Christ’s cross. On the verso is another study which shows the Virgin standing in profile with arms outstretched before her, almost like a sleepwalking Lady Macbeth; staining from the folds of her robe are visible in the top of the sheet.

Executed with astonishing confidence, this boldly worked ink drawing shows Romney’s mastery as a draughtsman. The drawing’s emphasis on the plaintive expression and gesture of the Virgin suggests his skill at evoking emotion. In his description of the Virgin’s robes, Romney gave form to the mournful tone of his subject with heavy, descending lines that pool at the bottom, giving the Virgin a statuesque quality. Preserved in outstanding condition, this richly inked drawing remained in Romney’s studio at his death before passing to his son. It is one of the largest and most outstanding sheets by Romney to remain in a private collection.