These two print studies exemplify Chéron's role as the leading teacher of life drawing in 1720s London. Chéron had come to England in the 1690s as a decorative painter and worked on the interiors at Boughton and Ditton for Ralph Montagu, 1st Duke of Montagu. However, Chéron's reputation ultimately came to rest on his work of the 1710s and 1720s at the Great Queen Street Academy and its immediate successors.

Chéron was a French Protestant who had studied in Rome for many years 'after the Antique & Raphael & other great Masters, whereby he acquired a noble great manner of designing: in the Accadamy at Rome he was much esteemed for his correct drawing. & gain'd the highest prize. in opposition to Remond Le fage who was then his antagonist.' After settling in England, though, Chéron's decorative paintings at Boughton and elsewhere were not judged successful enough to sustain him as a decorative painter. The problem, according to Vertue, was that Chéron was such a pure student of the Roman approach to drawing that he had neglected to learn colouring, for 'at Rome that is not thought so valuable or estimable as designing.' However, this weakness became Chéron's great strength when the drawing academy was established at Great Queen Street in 1711 under Sir Godfrey Kneller's leadership. There Chéron 'soon distinguishd his talent in delineing. being very assiduous. he was much imitated by the Young people. & indeed on that account by all other lovers of Art much esteem'd & from thence rais'd his reputation got into good business. was particularly much imploy'd for designs for Engravers.'

After the Great Queen Street Academy collapsed acrimoniously in 1718, Sir James Thornhill attempted to continue tuition at his own house, but abandoned this in 1720. Chéron and John Vanderbank then themselves established a new academy, off St Martin's Lane, which gained royal approval in 1722 with a visit from the Prince of Wales. These two drawings reflect Chéron's insistence as a teacher on an anatomical rigour that previous London academies had lacked. The anatomist William Cheselden had attended life classes at Great Queen Street and in 1720 Chéron endorsed a project by Philippe Richard Frémont to publish anatomical plates after drawings he had made at the London and Paris academies. Among the young generation who came under Chéron's influence were John Vanderbank, Gerard Vandergucht, Joseph Highmore, Elisha Kirkall and Bernard Baron '& several others as well Painters as Engravers benefitted much by his drawing.' Chéron's success was short-lived for the St Martin's Lane Academy failed in 1724 after the indebted Vanderbank absconded whilst Chéron was to die the following year.

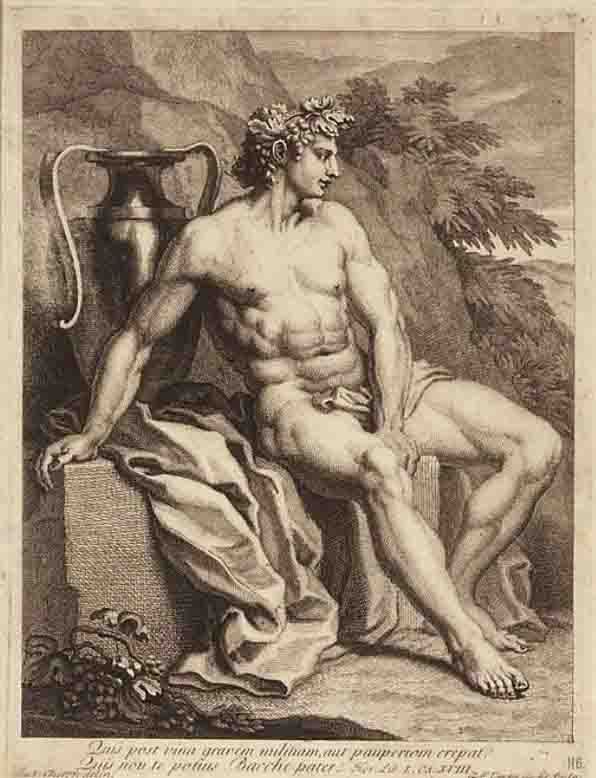

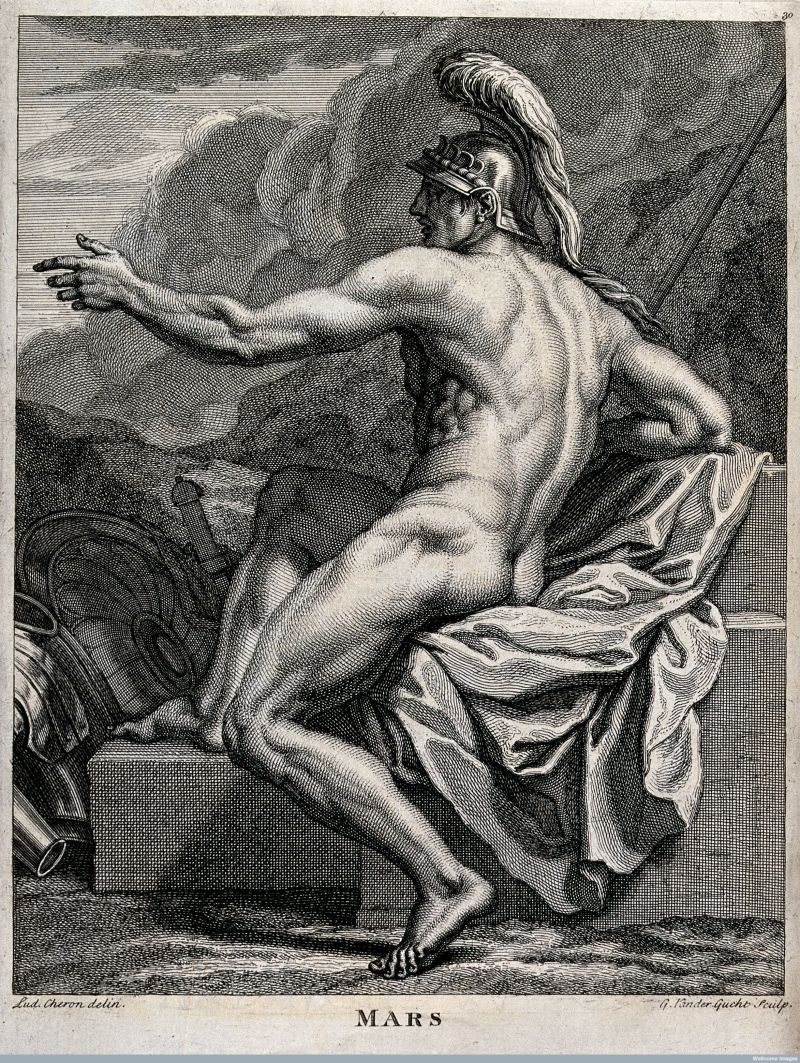

These two sheets, reduced versions of life drawings that Chéron made in one of the London academies were made in preparation for prints; both drawings were etched by Gerard Vandergucht in 1722 or 1725. The warrior figure is based on a life drawing now in the British Museum, from an album of life drawings and historical compositions by Chéron. The source drawing for the figure of Bacchus has not been identified. The British Museum album was the final and most valuable lot of Chéron’s posthumous sale, it eventually fetched the huge sum of 265 guineas. This suggests both the level of interest in Chéron as an artist and the value placed upon his life drawings immediately after his death and gives important context for Vandergurcht’s prints.

The engraver Vandergucht was closely associated with Chéron, having been taught drawing by him. He had joined the Great Queen Street Academy in 1713, at the same time as Vertue who recorded that Vandergucht 'by means of his drawing distinguished himself from many other young men that learnt in that accademy' and shook off the stiff manner he had learned from his father, the engraver Michael Vandergucht. Only a few weeks after Chéron's death in 1725, 'six Academy Figures with a Frontispiece, drawn from the Life by the late Mr.Cheron' were advertised for sale. That among these six were the prints after our two drawings is strongly suggested by a newspaper advert which appeared a few months later, which named 'Gerard Vander Gucht in Queen Street, Bloomsbury, of whom may be had a Set of Academy Figures, drawn from the Life, by the late Mons. Louis Cheron, and engraved by G.Vander Gucht.' Confirmation is provided by the recent appearance at auction of a bound copy of these six prints with its frontispiece, which is dedicated to Dr Richard Mead. The identity of the dedicatee, who was both one of London's leading physicians and a major collector of drawings, underlines Chéron's commitment to anatomical study.

The print of the warrior in the 1725 publication appeared not as Mars but as a figure of impious fury ('furor impius') accompanied by a quotation from Virgil's Aeneid, Book 1. It follows, then, that the warrior print was issued more than once, in different guises. Perhaps it appeared first as Mars, for writing in 1722 Vertue judged that Vandergucht's 'Figures done from Cherons Accademy Figures. are well & some of the first and last things of him [i.e. best and latest] that has yet appeard.' It could be that Chéron planned to issue a group of six or more academy figures in 1725, perhaps as a way of extending the reach of his teaching after the St Martin's Lane Academy had ceased the year before. Certainly this pair of drawings are carefully squared for an engraver and Chéron has adapted his large chalk life studies into bold, graphic figures complete with antique attributes. Alternatively, Vandergucht may have taken the opportunity to publish these figures in the immediate wake of Chéron's death, as a memorial to a then newsworthy figure. Vandergucht continued to publish and sell works after Chéron, such as 'four prints of the Acts of the Apostles' in 1728, and in the early 1730s a set of the Labours of Hercules Chéron had left unfinished at his death.