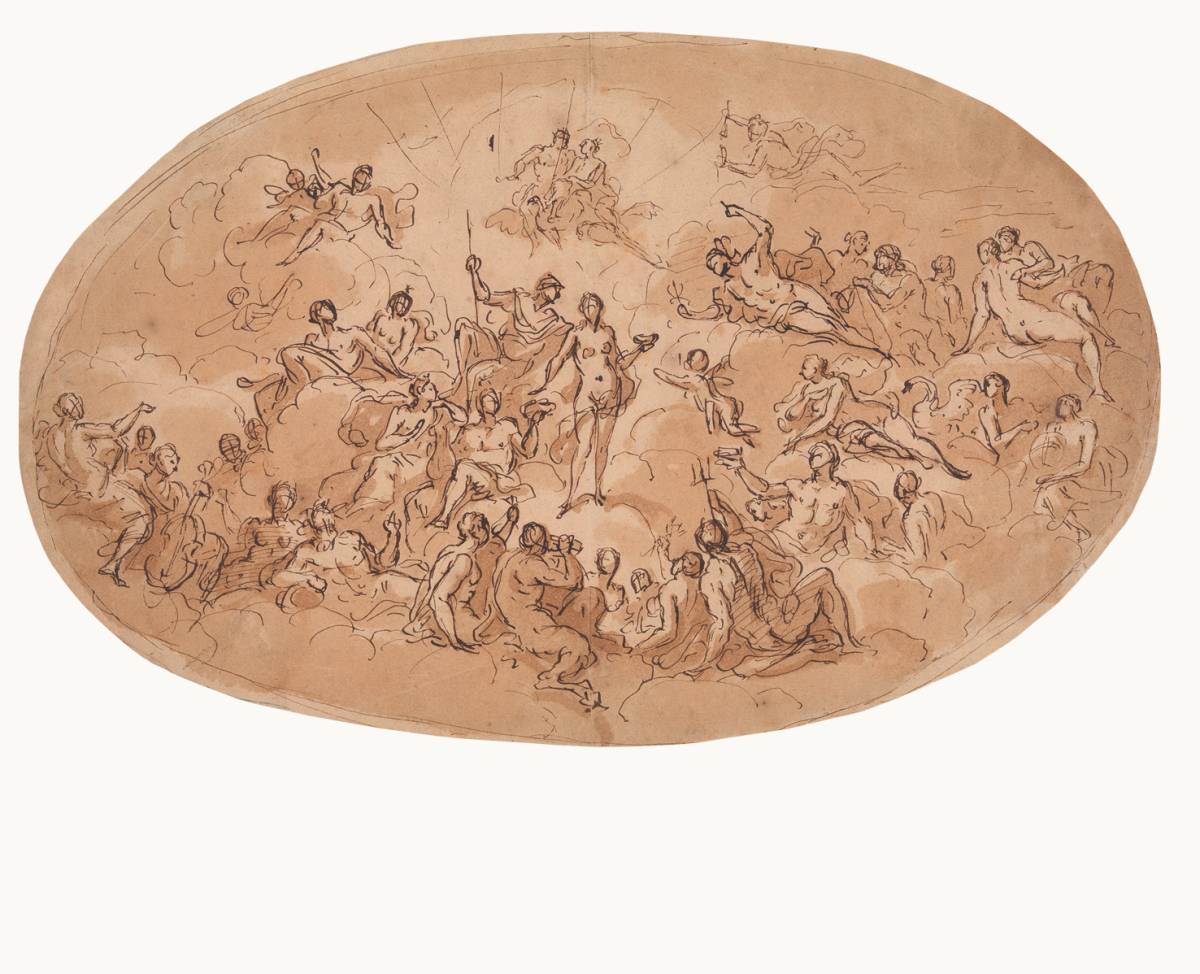

This ceiling study represents the reception of Psyche into Olympus, among an assembly of the gods. This was the subject of Raphael's famous ceiling at the Villa Farnesina in Rome and became a popular theme for baroque decorative painters in England. Louis Laguerre, for example, painted 'when Mercury take upe Physke in to heauen withe some cupides' at Castle Bromwich in 1699, and Thornhill himself selected it for his important early commission for Thomas Foley MP at Stoke Edith in Herefordshire.[1] It is possible that Thornhill drew this study for Stoke Edith, but the destruction of the interiors by fire in 1927 makes an assessment of its role uncertain. The oval shape of this study argues against a link to Stoke Edith, where the hall was a two-storey cube so that the ceiling would have been square rather than oblong.[2] On the other hand, an oval ceiling design from the collection of Sir Brinsley Ford, on the subject of Cupid and Psyche, has also been associated with Stoke Edith.[3]

Most of Thornhill's surviving preparatory drawings represent his attempts to arrive at the most satisfactory arrangement and grouping of classical gods. Thornhill was a relentless experimenter with approaches to composition, and could make many rough sketches of alternate groupings of an allegorical scene. What makes this drawing interesting, though, is that Thornhill has already resolved the composition, and does not make corrections to any parts of it. Instead, he is concerned with the potential for the flow of light to cohere and structure the space. To achieve this, Thornhill has applied a thin wash very quickly and with a very wet brush so that it covers the sheet evenly. The potential for light to provide a unifying structure for large-scale allegorical history painting was exploited by Thornhill successfully in dramatically-lit works such as the east end of the chapel at All Souls' College, Oxford, where an intense heavenly light from above throws the rest of the scene into dark relief.[4]

References

- Edward Croft-Murray, Decorative Painting in England 1537-1837, London, 1962, vol. 1, pp.62-3; William Osmun, A Study of the Work of Sir James Thornhill, unpublished PhD thesis, 1950, vol.I, p.441.

- William Osmun, A Study of the Work of Sir James Thornhill, unpublished PhD thesis, 1950, vol.I, p.441.

- Brinsley Ford, John Ingamells, Francis Russell, John Christian, Nicholas Penny, Jennifer Montagu, Howard Coutts, Timothy Wilson and Dudley Dodd, 'The Ford Collection - II', Walpole Society, 1998, vol 60, p.241.

- Klara Garas, 'Two Unknown Works by James Thornhill', The Burlington Magazine, November 1987, vol 129, no 1016, fig 23.